I am passionate about protein traffic, so much so that I invested four years of my life to research about it during my PhD in the Netherlands. Being a scientist is like being Sherlock Holmes: each new clue takes you to the next until the mystery is solved. Following the steps of the famous detective, during my doctoral studies I discovered a molecular mechanism that plays a crucial role during memory storage in the brain.

During my postdoctoral research in Cambridge Stem Cell Institute (UK), I applied my knowledge of protein traffic to tumour development in intestinal stem cells. For this project I needed to use a research model that more closely represented real-world conditions and that allows for easily identification of genes responsible for the tumour growth. The best experimental model that could achieve that objective was an animal, in my case a mouse. Broadly, my project sought to remove a specific gene from the mouse genome to study whether it affects tumour development in intestinal stem cells. The intestine is formed of different cell types each of which have a specific function, which combine to create a properly functioning organ. When intestinal stem cells are cultivated under specific conditions in the lab, they can generate all the different cell types of the intestine in a laboratory plate forming a three dimensional culture. We scientists call this novel culture technique “organoids” to differentiate it from the traditional cell cultures which are composed of one single cell type.

Experimental mice bred in an approved animal facility

In my research project, as in many others, animal models help us to confirm that what we demonstrated in a laboratory plate also happens in the whole organism. This is so since animals share same organs and sistems as we do and are afflicted by same diseases. Before I could start investigating with animals, I was legally obliged to undertake training to learn about the different animal species used in the laboratory, their needs, how to recognise pain symptoms, techniques to avoid causing pain and the strict scientific, ethical, and legal requirements that regulate this research. These regulations are designed to ensure that animals are only used in research if:

- There is no alternative method accepted by the European Union that provides the same results without the use of animals

- The potential benefits outweigh the potential suffering caused to the animals

- It is performed according to the 3Rs principle, which states that animals must be replaced with alternative methods whenever possible, that the number of animals must be reduced to the minimum that is statistically appropriate, and that all scientific procedures are refined in order to reduce any pain, suffering or distress in the animal

- It is performed by highly qualified personnel under veterinary supervision in facilities that are fit for purpose for each specific species.

While my research project was progressing, I started to realised that despite the strict regulations that apply to this work, society was polarised about animal research. There seemed to be a widespread lack of understanding which could perhaps be attributed in part to the fact that very few research centres and organisations provided information about the topic. If the scientific community does not stand up and participate in the public dialogue, explaining how animal research is performed, what the regulations are and why these models are essential for research aimed at preventing, diagnosing, and treating disease in humans and animals, it is unsurprising that many citizens do not understand or support these practices.

A lack of information can have dangerous consequences. A clear example is last year’s European Citizens Initiative ‘Stop Vivisection’. By collecting 1.2 million signatures, the petition organisers – a handful of animal rights organisations – could demand that the European Commission abrogated Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used in scientific procedures and develop a new legislative framework that does away with animal research. The petition intended to pass a message that animal research is bad research, not relevant for humans and easily replaced by alternative methods. The petition omitted to explain that the majority of drugs, treatments and surgical procedures that we benefit from today have been developed thanks to research on animals and that, in many cases, appropriate, practical alternative methods are not yet available.

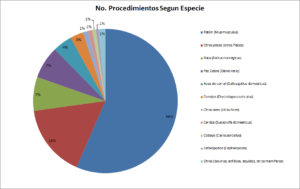

Figure 1. Percentage of animals – by species – used in Spanish research during 2014.

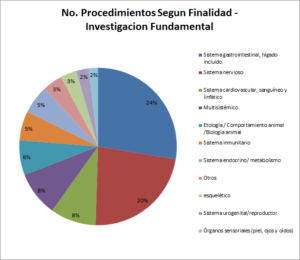

When I started working at the European Animal Research Association (EARA), I quickly learned a huge amount about how animal research is performed and regulated in other European countries. In Spain, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Environment is the competent authority that oversees these practices. The Ministry publishes annual statistics on the use of animals in scientific research in Spain. The figures show (see Figure 1) that, as in other European countries, mice continue to be the dominant species, making up 56% of all animals used. Perhaps surprisingly, fish are the next most used species, representing 16% of research models in Spain (23% when including zebrafish in the count), followed by rats at 7%. The majority of these animals (see Figure 2) are used in fundamental research at universities and public research centres which seek to decipher the complex biological mechanisms that lie beneath diseases such as Hepatitis, Chrone’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, hyperthyroidism and AIDS, among many others.

Figure 2. Percentage of animals – by research purpose – used in Spanish research during 2014.

As clearly stated in the European Commission’s response to the ‘Stop Vivisection’ petition in June last year, animal research continues to be necessary to advance medical science and to evaluate the safety of new drugs. In its response, the Commission stated that, despite the ultimate goal of European Directive 2010/63 being to phase out animal research, alternative methods cannot yet fully replace animal models. In order to achieve the ultimate goal of replacing animal research, the Commission announced four goals they will pursue: to facilitate information sharing to progress the 3Rs; to accelerate the development, implementation and validation of alternative methods by supporting research in this area with EU programmes; to ensure compliance with the Directive especially regarding implementation of 3Rs; and to organise a scientific conference to engage the scientific community.

After the turmoil that the ‘Stop Vivisection’ petition caused in Europe, the scientific community recognised the need to engage in the public debate and to provide more information. In September this year, the Spanish Confederation of Scientific Societies and Organisations launched a transparency agreement on the use of animals in scientific research. I am positive that this agreement – which has already been signed by more than 100 organisations, public research centres and universities – will help to improve public attitudes towards the use of animals for important research where no alternative is available and to improve public understanding of why this kind of research is done and the benefits that it can bring.

By Dr Emma Martínez Sánchez, Communications and Policy Officer, The European Animal Research Association (EARA). SRUK Chair Science Policy Committee.

Related news:

“The case for scientists engagement in animal research policy making”, EARA

“¿Por qué se utilizan perros y gatos en investigación?” El País

“Por qué tanto revuelo con la experimentación animal?”, Materia (El País)

“Experimentar con animales es ‘vital’, según los científicos españoles”, Hipertextual