Imagine that you are young, you watch your diet, do sports, and you even take the medication that your doctor has prescribed for your high triglyceride levels. And yet, test after test, everything remains the same and your triglyceride levels do not drop. If you feel identified, do not despair: your body may be trying to trick your doctor, and your genetics are simply responsible for it.

Our research group at the Miguel Servet Hospital is dedicated to studying diseases related to cholesterol and triglycerides and finding out the possible genetic causes that may lie behind them. First of all, it is important to note that the cholesterol and triglyceride levels of these patients are not easily controlled with standard drugs. Therefore, in order to have a more detailed description about each patient’s situation, we evaluate their family history, carry out a personal physical examination (as well as personal and family history), and classify them into different groups according to their cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

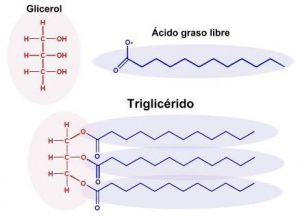

One of these diseases that we have recently studied is known as pseudo hypertriglyceridemia [1]. This disease only occurs in young men who, despite having a normal weight and a good diet, have very high triglyceride levels. Specifically, pseudo hypertriglyceridemia is caused by a mutation in a gene known as Glycerol Kinase [2]. This gene is located on the X chromosome, which means that only men can suffer from this disease. Patients with this mutation do not experience any symptoms in their day-to-day lives, but they unfortunately do have high levels of a molecule called glycerol; and this is where the problem lies! The high presence of glycerol interferes with the correct diagnosis of triglycerides in the blood as it amplifies its detection. As glycerol is the molecule detected in routine tests, it is common practise to infer that the number of glycerol molecules is equal to the number of triglycerides. Glycerol is fooling us here! Consequently, the these patients’ test results show very high triglyceride levels that are not real and are incorrectly diagnosed as hypertriglyceridemic (see Figure 1).

To identify this type of patient as soon as possible, our research group has created an evaluation system to which the GP has access [3]. So then… How does this evaluation system work? First, there are good chances patients are diagnosed with this disease if they meet the following criteria: (1) being a young male (under 40) with normal weight who has been given medication to lower high triglyceride levels without success and (2) having normal glucose values, elevated HDL cholesterol (the so-called “good cholesterol”), and normal levels of liver enzymes (you may check this guide (Spanish version only) for more information). These markers are obtained from a routine blood test. To evaluate the possibility of pseudo-hypertriglyceridemia among patients, we have developed a scoring scale from 0 to 14 based on the criteria mentioned above and the results obtained with the blood test. Thus, all those subjects with a score greater than 10 have a high probability of presenting the disease. However, the definitive diagnosis is confirmed by a specific genetic analysis that allows to identify the mutation in the Glycerol Kinase gene.

Once the correct diagnosis is confirmed, both the patient and their doctor will know that no medication is necessary. Instead, they will at last be aware that those elevated triglyceride levels that were detected throughout the patient’s life in the analyses were not real. With this research, we wanted to give a practical, clinical, and manageable application to primary care doctors to help them with the immense work they do, as well as to prevent our body and our genetics from being able, at some point, to mislead or deceive them.

By Itziar Lamiquiz Moneo, post-doctoral researcher at CIBERCV (IIS Aragón), Miguel Servet Hospital (Spain).

More information: