We are functioning beings thanks to a collection of mechanisms that keep our body breathing, moving and thinking. It is not only one but several events occurring at the same time that allow our cells, organs and systems to perform their specific functions and so, a simple action such as eating an apple can impact the function of our stomach, our pancreas, our intestine, our muscles and even of our brain. This interconnection is also present during disease. An existing disease in the body of a person can be altered by another completely unrelated condition. A perfect example of this is dementia, and more specifically of Alzheimer’s disease. In recent years, people have realized that Alzheimer’s disease can be aggravated by infections occurring outside of the brain, for instance a urinary tract infection or a chest infection, but we are still not sure why.

Before the plot thickens, let me tell you a bit about dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia is a syndrome that affects brain function, which is reflected as memory loss and detriment of abilities such as comprehension, language, orientation and judgement. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are currently around 50 million people living with dementia and although dementia mainly affects older adults, it is not a normal part of the ageing process [1]. There are many forms of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease is the most common one of them. To date, we do not know exactly what causes Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, but scientists all over the world, including us, are working hard to find this out.

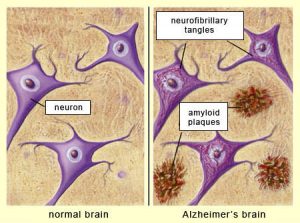

For many years, the main suspects behind Alzheimer’s disease were the amyloid-beta and tau proteins. These two proteins are present in the brain under normal conditions, but in a brain with Alzheimer’s disease, they are found clumped together, in the form of toxic “plaques” and “neurofibrillary tangles” that can cause malfunction and death of brain cells. Even though a lot of research has been done to know how amyloid-beta and tau clumps are involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, we are still not sure; moreover, researchers have realized that these two proteins may not be the only culprits and have started to look at other mechanisms that could trigger or participate in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is the main form of dementia and is characterized by the presence of protein clumps, known as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, in the brain. Image obtained from http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/d/d_08/d_08_cl/d_08_cl_alz/d_08_cl_alz.html

One of the things that clinicians and researchers started noticing in patients with Alzheimer’s disease was that their symptoms suddenly got worse following an infection occurring outside of the brain, like a urinary tract infection or a chest infection. In young people, infections cause pain and fever as a result of the immune system activation, but in older adults, they can cause what is known as delirium, which is a state of confusion, agitation and disorientation. Usually, delirium symptoms get better over a few weeks, but delirium in an old adult with Alzheimer’s disease can have lasting consequences, speeding up brain damage and accelerating the progression of the disease.

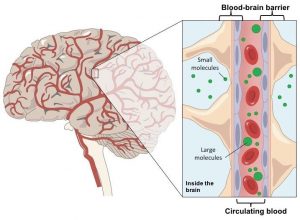

How can an infection somewhere else in the body reach the brain and have such a strong negative effect on its function? The answer could be in the blood-brain barrier, a border between the brain and the circulating blood that protects the brain. This barrier is highly selective and semipermeable, meaning that only specific molecules can be transported through it, keeping away things that could damage the brain. When young, our blood-brain barrier is like a new coffee filter that only lets the water and very small coffee components through it; as we age, the blood-brain barrier becomes leaky, and just as a used coffee filter that lets the big coffee particles through, a leaky blood-brain barrier allows harmful things to enter the brain.

The blood-brain barrier separates the brain from the circulating blood and it only allows molecules from a specific size to move across. Image obtained and modified from https://ib.bioninja.com.au/options/option-a-neurobiology-and/a2-the-human-brain/blood-brain-barrier.html

In an old person with Alzheimer’s disease, a leaky blood-brain barrier and a vulnerable brain are not a good combination. When an Alzheimer’s disease patient has a urinary tract infection or chest infection, their body tries to fight back by activating the immune system. Cells and other components from the immune system travel through the blood stream all the way to the brain and can easily cross the defective blood-brain barrier. Once in the brain, these components could promote changes that end up in damage to brain cells, causing delirium and worsening the signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

There are still a lot of unanswered questions in this matter: we do not know why and how the blood-brain barrier becomes leaky in a diseased brain, and we do not know exactly how components from the immune system cause damage when they reach and enter the brain, but it is very important to keep looking into these mechanisms. The link between infections somewhere else in the body and damage in the brain of people with Alzheimer’s disease is the perfect example to remind us that in our body, everything is interconnected.

Post by Dr Irina Vazquez Villaseñor, postdoctoral researcher at the Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience, University of Sheffield.

More info:

- World Health Organization. Towards a dementia plan: a WHO guide [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018. 71 p.