In modern Western societies it is often emphasized that the individual is solely responsible for their successes as well as their failures. Although this may be empowering, it can generate an intense sense of guilt. The pressure to avoid failure can lead to unsustainable lifestyles that ignore the limitations that the body imposes. In recent years, however, people have become more aware of the stresses on physical and mental health in various aspects of their life, like the workplace. The scientific community is one of the groups that has identified the existence of an unhealthy work dynamic within their own guild, where it is very common. It is often the youngest scientists, as they begin their research career, the most prone to such practices. That is why the impact on their health has been recently assessed.

“I suffer from stress at work and I am not a scientist; is it really so different in research positions?”

A recurring question is whether the scientific profession really differs so much from others, and if so, why is this the case. It is true that there are no stress-free professions, each case is different, and different people have different methods to deal with complicated situations. Still, the data tells us that, in the early years of their career, scientists have a higher risk of suffering from psychological disorders – such us anxiety and depression – compared to the rest of the population.

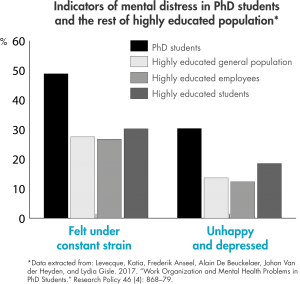

If we delve into the evidence, a 2017 study [1] explored the prevalence of problems related to mental health in a representative sample of graduate students in Belgium compared to other population groups with higher education. This work predicted that 32% of doctoral students had a high risk of suffering from a common psychological disorder, especially depression (a percentage significantly higher than the other population groups). The graph below (Fig. 1) shows how those groups compare to each other related to two of the indicators from the study.

Figure 1. Results of the evaluation of mental distress in a population sample. Chart based on the data published by Levecque et al., 2017.

In a later article, published in Nature Biotechnology [2], a sample of more than 2000 students was analyzed, including a high percentage of those studying a PhD, reached similar conclusions. This study identified that the group of postgraduate students was six times more likely to experience anxiety and depression compared to the rest of the population. In addition, it revealed that 39% of students suffered from symptoms of moderate to severe depression (the percentage in the general population was only 6%).

In November 2019, Nature magazine published an article [3] based on the survey with the highest participation to date on this topic. In it, 6000 pre-doctoral students responded to issues that had to do, not only with stress indicators, but also satisfaction with various aspects of their doctorate. As one might imagine in a highly vocational profession, not all was a cause for concern: 75% of respondents said they were very or somewhat satisfied. It is also worth mentioning that 36% of them suffered from symptoms of anxiety or depression.

What are the underlying causes and how can we improve the situation?

There are some common factors that affect researchers at work. Some of them have to do with job insecurity: a less competitive salary than in professions that require a similar qualification, the uncertainty of short-term contracts or the need, on many occasions, to move to another city or country, when the contract ends… Others relate to the high level of demand imposed by the system of publications for which scientific merits are evaluated (on which the next contract can depend). Other subtler conditions, such as the diffuse barrier that exists between the personal and the professional life, blurring the lines of what we consider a working day, may enter as well into the well-being equation. Professional successes and misadventures can be tied strongly to with self-worth.

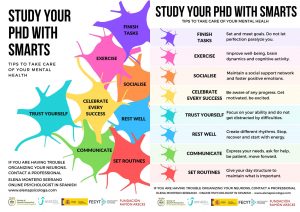

Researchers “face a very broad challenge, not comparable to any of the situations faced so far, and with many difficulties that must be solved by themselves”, says the psychologist Elena Montero [4], founder of the clinic Sentido Psicología. According to Elena, “the milestones throughout a doctorate are diffuse and very distant, while the perception of resources, both material and human, is limited. All this results in a sense of helplessness and significant wear.” In the guide below (Fig. 2), she gives practical advice on how PhD students can take action to improve their well-being.

Figure 2. Graph designed by psychologist Elena Montero with a series of tips that PhD students can follow to improve their well-being.

In countries like the United Kingdom, universities have long established systems to cope with the demand on the mental well-being of staff and students. The Imperial College and the University College of London, for example, offer psychological assistance services [5] [6], as well as the University of Edinburgh [7]. However, even those services may be insufficient. For this reason, the Spanish Researchers in the United Kingdom (SRUK/CERU) and other non-profit organizations are contributing to tackle the problem. SRUK/CERU has been offering a mentoring program [8] to pave the way for students and scientists who request it. In addition, it has organized events for raising awareness and counselling [9] [10]. Following previous actions, the Marie Curie Alumni organization is hosting a day long workshop on researchers’ well-being and research culture this March [11].

Unfortunately, Spain does not yet have the level of institutional support found in the United Kingdom. For this reason, the citizens’ initiative is especially important. As an example, the Scientists Dating Forum (SciDF), an organization based in Barcelona and aimed at raising awareness of science as a driver for change, has conducted several workshops to advise doctoral students during the last year [12].

In spite of how worrying the figures are, an indicative of a positive trend is that more thorough studies are being carried out and measures are being taken to act on the problem. However, some of the conditions, the system of publications and evaluation of scientific merits, for instance, require profound changes that affect how scientific activity is conceived today. For this reason, the involvement of all responsible actors will be key to continue doing quality science with more satisfied scientists.

* * *

By Berta Gallego Páramo (@bertagallegop), PhD in Vegetal Physiology and developer of scientific applied tools at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (London).

More information:

- Levecque et al., 2017.

- Evans et al., 2019.

- Woolston 2019.

- Elena Montero’s website, psychologist who ran the workshop detailed in the text.

- Counselling service at the Imperial College (London).

- Psychological and counselling service at the University College of London.

- Counselling service at the University of Edinburgh.

- SRUK’s mentoring program.

- Mental health round table organized by SRUK.

- Mental health workshop organized by SRUK.

- Wellbeing workshop organized by Marie Curie Alumni.

- Mental health workshops organized by Scientists Dating Forum.