We often hear news about the discovery of a very promising treatment against cancer, diabetes or Alzheimer. But then, for a very long time nothing else is heard about it: has this promising treatment been forgotten? Why does it take so long to bring new drugs to the market? In this post I will explain the process that pharmaceutical companies follow when they want to bring new drugs to market.

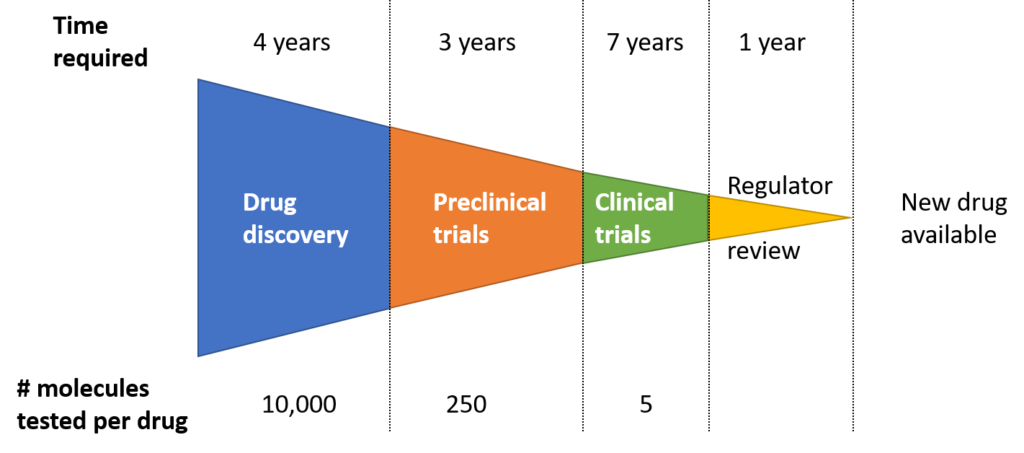

To begin with, we need to understand what is happening in the body during the disease to choose a target, normally a protein. Changing the activity of the target can stop the disease. Once the target is known, the search for molecules that interact with this target begins! These molecules (called hits), are found by testing a very large number of compounds against the target. They will then be optimized to be as active as possible against the target.

The compounds then enter pre-clinical trials, where they are tested in animals. This step is important to confirm the fact that changing the target stops the disease in animals and to make sure the compounds are not toxic. Almost anything that enters our bodies can be toxic at high concentrations, even water. Pre-clinical trials lead into clinical trials with people, and this is the longest and most expensive phase of the process!

In clinical trials, the compound is first tested in a small group of healthy volunteers, to confirm that the drug is not toxic in humans. Although this is normally safe, if not done correctly it can go very wrong. Some years ago, a trial in France didn’t follow procedures and things went very wrong; several people ended with brain damage. In a second phase, the compound is tested on a small number of volunteers that have the disease. During this phase, we confirm that the drug stops the disease in humans. At this stage many compounds are discontinued because they show no effect in humans, despite being very promising in the lab and in animals. In the final phase, the compound is compared against the typical treatment or placebo, normally a sugar pill, in a large group of patients. Comparing against placebo is important because in some cases just thinking you are being treated is enough to cure the disease, the body is amazing! Still, there is a chance that the compound will fail to show that it is a better treatment than the currently available ones and is therefore abandoned.

The final stage before a drug can reach the market is convincing government regulators. The FDA in USA and the EMA in the EU need to approve its use before a compound can be sold in these markets. To obtain the approval, the companies need to give these agencies all the data collected to prove that their drug is safe and effective.

I have not told you yet about how long each of these steps takes. In general, the whole process can take up to twenty years. From that, the clinical trials are the stages taking the longest, up to a decade in some cases. Also, the chances that any molecule will pass the whole process is tiny. Even molecules that pass preclinical trials only become a drug around 20% of the time.

To shorten this time and develop drugs faster, many scientists look to reuse drugs in the market for new diseases. One example is thalidomide. It was used many decades ago against morning sickness on pregnant women. Later, it was discovered that it was harmful to unborn babies and its was taken off the market. However, today it is sometimes used on cancer patients and against leprosy. By using a known drug, there is already a lot of data about toxicity in humans and you only need to prove activity against the disease.

I hope this post has convinced you that bringing a new drug is a long process, but this is to make as sure as possible that nothing toxic reaches patients. The problem is that scientist, when they discover a new compound that could become a drug, want to share the good news. That means news of promising treatments come a decade before it can reach the market, and the news do not tend to mention this fact. This wait is not out of greed or laziness, but out of concern for everyone.

By Dr Antonio de la Vega León. Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Sheffield. SRUK Yorkshire Constituency.