“Everyone is a genious, but if you judge a fish on its capacity to climb a tree it will live its whole life thinking it’s an idiot”

A graduate student is six times more likely to experience depression and anxiety than the general population, according to a study published in Nature Biotechnology (1) in March this year (2). Of the total students analysed (coming form different North American universities), 41% suffered from moderate to severe anxiety or depression, as opposed to the 6% of the general population suffering similar conditions. The publication of this study had a massive response (3) in Twitter and gave rise to an Editorial in the prestigious journal Nature (4) about the necessity of finding solutions to avoid, or at least decrease, these alarming numbers. Is this exclusively a student’s problem or is it common to all stages of the scientific career? What could we do to improve the mental health of the research community?

There are probably many answers to these questions and many debates should be opened. However, in my personal opinion, one of the key elements associated to research “unhappiness” is its (almost total) lack of connection with creativity. A creative person can be defined as someone capable of finding novel connexions or associations, that are unique and original. Isn’t that what researchers do? If we ask researchers whether they define their work as creative, they will almost all give a positive answer. But if you ask the same people if they consider themselves creative, probably no more than 20% of the hands would rise, at most. How can this be possible? How can it be that we (researchers) are doing such a creative activity as science, constantly searching for new theories, applications or models without being aware of our own creative abilities?

From these disconnections arose a project called seisques (5) set up by a group of interdisciplinary researchers, educators and artists. From this group we wanted to design tools to help uncover creative potential in those areas that really should be “intrinsically” creative, such as research.

Participants of the Creative Research Workshop, done by seisques in collaboration with SRUK-London. Blizard Institute, London. Photo by seisques.

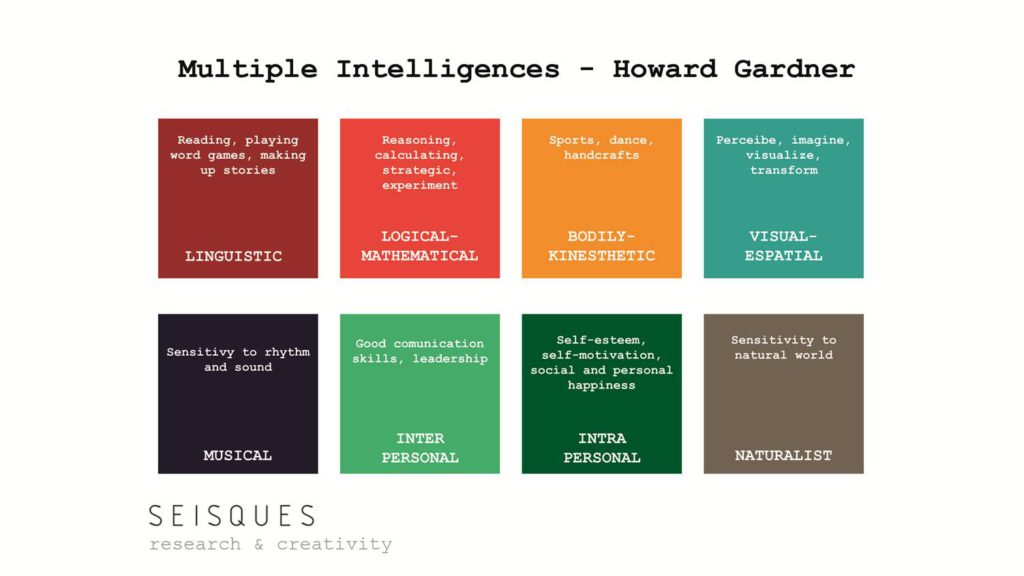

The neuroscientist Nancy C. Andreasen has studied the brain looking for the keys of creativity (6). According to her studies, creativity is not associated with having a high score in IQ tests, and there is no such unique characteristic that makes a “genius”. The ideal background to trigger a creative process implies having an extreme curiosity, many interests and an intellectually rich environment, that allows the free exchange of ideas. Also, by studying the lives of several “geniuses”, Andreasen found some repetitive patterns, for example, that their bright ideas appeared in relaxing moments or when doing pleasant activities, and not when they were highly concentrated and working (6). That’s interesting! On the other hand, the psychologist and Professor at Harvard University Howard Gardner has systematized the theory of multiple intelligences (7). Such theory claims that we have eight types of intelligence, rather than just the one measured by the IQ test that Andreasen speaks about, and that each intelligence works semi-autonomously in our brain. Thus, each person will tend to solve complex situations using their more developed intelligence or ability. Is indeed important to understand in which manner we are intelligent, to improve those intelligence types that we have less developed, and to try to work with people that have complementary intelligences to us, as they will give us novel perspectives and answers.

Characteristics of the eight types of intelligence described by H. Gardner. Photo by seisques.

Andreasen’s and Gardner’s research should surely broaden our creative self-awareness. But there is still one key question: how do we induce our mind to operate creatively? Edward de Bono, psychologist and professor at Oxford University, talks about the necessity of learning to use the lateral or creative thinking (8). Nowadays we tend to believe that through a simple accumulation of knowledge we will be able, almost magically, to create new models or ideas, and we normally use what he called vertical or logical thinking. Such way of using your brain is useful to collect, validate or handle already-known ideas, but is not going to help us to create something different. The key to creating something novel is to use the information differently, learning techniques that induce the restructuring of information and step out of the restrictive and rigid mechanisms normally used by our brain. The tools de Bono propose to implement lateral thinking are the ingenious, insightful and fun. Even more interesting! This type of thinking must be learned and trained (similar to learning mathematical thinking) to develop our mental attitudes to creativity. Therefore, both Nancy C Anderson and Edward de Bono suggest multiple exercises in their books that could help us cultivate our creative mind (6,8).

Tesis Take-away, an experience about the formats and dissemination of the academic research done by seisques as part of the “Ni arte ni educación” exhibition (10). Matadero, Madrid. Photo by seisques.

In conclusion, it is imperative to connect science with creativity. To do so, we must recognise and value all our intelligences, understanding how our “unique” way of solving questions are valid. We must allow curiosity and enjoyment in research, and create environments where a truly rich and free exchange of ideas can occur, even coming up with new formats for those exchanges. Also, we should include educational programs that boost creativity on the new research generations and train supervisors to understand the potential and incentivise creativity (9). All these measures will help us, not only to improve the mental health of the research community but also to improve the scientific quality of the research itself.

By Dr. Alba Maiques-Diaz. Postdoctoral Fellow, Leukaemia Biology Group, Cancer research UK Manchester Institute. Co-founder of seisques. Northwest SRUK Constituency.

More information:

1. https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt.4089

2. Evans TM., Bira L., Weiss LT., Vanderford NL. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology 36, 282–284, 2018.

3. https://twitter.com/NatureNews/status/978212558938296321

4. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-04023-5

5. https://twitter.com/seisques

6. Nancy C Andreasen. The creative Brain, the neuroscience of genious. Plume, 2006

7. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IfzrN2yMBaQ

8. https://www.edwddebono.com/

9. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/study/graduate-school/public/creative-research/Supervisors-and-PI-(2).pdf

10. http://www.niartenieducacion.com/