The 11th of February is the International Day of Women and Girls in Science. As many other institutions, the Society of Spanish Researchers in the United Kingdom Society (SRUK) joined the commemoration activities prepared for this day. At the Oxford constituency, we organized a tour around this historical city visiting emblematic places where female scientists worked helping to understand the world around us.

Women were allowed to attend classes at the University of Oxford since 1877, but surprisingly they could not fully enrol the university until 1920. As a curious fact, all the female students who had attended classes before enrolled that year, resulting in more than forty women graduating the same day they joined the university.

First graduated women at the University of Oxford

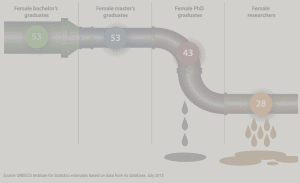

At the time, the number of female students in the university was limited to one per every six male students. Nowadays, the situation has improved considerably as there are not gender-specified limitations for students, and the number of women enrolled is higher that the number of men. As a result of this improvement women have not only been students, but have also been part of the research carried out in the university for the last 97 years. I would like to talk about some of them in order to inspire you.

Prof. Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Hodgkin is perhaps the most well-known female scientist at the University of Oxford. Dorothy graduated in Chemistry in 1928 and was awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1964 for her crystallographic study of penicillin and vitamin B12. Although she did her PhD in the University of Cambridge, she returned to Oxford in 1934 to establish an X-ray laboratory. There, the crystalline structures of insulin, penicillin and vitamin B12 (among other substances relevant to our health) were determined. Local newspapers, far from granting her the credit she deserved, titled the news about her Nobel prize as: “A housewife wins the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.” In addition, Dorothy Hodgkin was not only an exceptional scientist but also a great defender of human rights, in particular helping other female scientists in developing countries.

At the first half part of last Century, we find another very important female scientist in Oxford: Janet Vaughan.

Dr Janet Vaughan and her design for a transfusion bottle

During her days as a Medicine student, she already had difficulties to treat patients, as some of them did not trust a female doctor. Given this fact, Vaughan had to practice numerous times with pigeons instead of real patients. During her stay in London she designed the blood collection bottle for transfusions, a system that its named after her. Since 1945, her research centre was the Churchill University Hospital in Oxford where she continued to study blood problems. Her book, The Anemias, was one of the first specialized treaties on blood diseases.

Closer in time, we can point out another great female scientist, who is still a professor at Oxford University. She studied at the University of Edinburgh and her greatest scientific contribution came during her PhD at the University of Cambridge. I am referring to Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

Prof. Jocelyn Bell Burnell

Her case is more than exceptional, since her observations led to the discovery of the first radio signal of a pulsar (a type of neutron star that emits radiation periodically). Her work was awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1974, but unfairly, not to her. It was awarded to her supervisor, Prof. Antony Hewish. However, her contribution has been recognized by other organizations, including the or the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) in Spain.

Prof. Kay Davies

Finally, I want to highlight another great female scientist with more recent contributions in time: Kay Davies, whose genetic studies have helped strongly to understand the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). This disease is caused by a genetic mutation in the Dystrophin gene that produces a defective protein which progressively degenerates muscles. In the 1980s, Davies developed a test capable of examining foetuses whose mothers were at risk of carrying the mutation. At the end of that decade, her studies concluded that there is a smaller version of dystrophin – but still functional- called utrophin, which can compensate for the defects in dystrophin.

These female scientists are a small example of the many women who have contributed to scientific development and, therefore, today’s world. All of them are an example of struggle, personal overcoming and self-confidence. They are clear examples that women can and should continue to fight for a place right in our society. Scientists, housewives, lawyers, athletes …, all united for a more egalitarian future.

I hope this review about some of the most important female scientists who have studied, worked and lived in the city where I currently live inspires ourselves to advance in Science and in our society.

New generations at the University of Oxford

By Dr. Laura Martínez Maestro, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Physics Department, University of Oxford. SRUK Oxford Constituency.