I grew up in a city in the middle of Spain very far away from any coast, whatsoever marine environment. But I used to watch nature documentary films after school and I remember being totally amazed about the plenty of fish there were in the oceans in numbers, in species, in colours… However, these films were already flagging messages of the human impact on these amazing oceans. Despite those messages, we are still wondering how deep is that impact -even if there is any impact- and what are the consequences.

Today, I am going back in time to asses the gravity and speed of the human exploitation in the sea. To do that, my colleagues and I are looking at one fish that we know has gone down a lot in numbers: the European Hake (Merluccius merluccius L. 1758). According to the red list of threatened species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), European hake population is considered as declining and its stocks are mostly depleted or fully exploited in the Iberian Peninsula and the Canary Islands.

Archaeological hake samples in the collagen extraction process. (Photo: L. Llorente)

But, since when has this happened? Have we always been fishing hake with such intensity? Have hake stocks been affected by fishing activities in the past? Thanks to Archaeology (the study of the human past through the material record, including organic materials) and some specific chemical analyses we are trying to find out how and why the European hake has been affected by humans through time and space. For example, we can tell a lot about the numbers of a fish, if we know how the average length change through time.

Nowadays, with an average length between 30-60 cm, hake is considered one of the big fish of the supermarkets -until 1.5 kg of fish in the plate, not that bad you may think, right? The problem is that hake was more than 15 cm bigger in the Middle Ages and even in Roman times. And previous to the huge fish factories of the Roman empire, hake was even bigger. This not only means that the hake is smaller today but its biology could have changed as well. In order to evaluate if such a change happened, we are carrying out isotopic analyses on bone collagen preserved in archaeological hake bones from the Iberian Peninsula since the Neolithic up to to the XIXth century as well as from recent specimens. We check if any variation has occurred in the ratio between the different forms of carbon on the one hand, and nitrogen, on the other, of the main protein constituting the organic component of bones, the collagen. These analyses allow us to differentiate hake stocks from different regions and additionally to find out if the feeding behaviour of the hake has varied such as the species it prey upon to or their contribution to the hake diet. In other words, if the trophic level of the hake has not change or, on the contrary, this position has been affected by the size shift or else because of the preys hake used to fed on in the past are no as much available today. This way, hake is kind of an indicator of what is going on its environment.

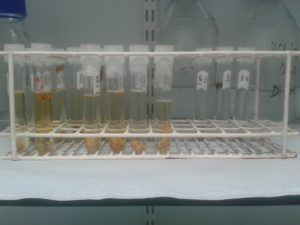

Capsuled collagen for isotopic analysis. (Photo: L. Llorente)

We do not have to forget our oceans hold a fish resource that provides food for almost half of the +7 billion people on the planet today. In a world of growing population, climate change will reshape marine diversity and fisheries production. We do not have time to break boundaries between disciplines, we need to to join forces to preserve biodiversity and ensure sustainable fisheries. Why not taking some lessons from the past to manage our oceans today… for the future.

By Dr Laura Llorente Rodríguez, Marie Curie Postdoctoral Researcher, BioArCh-Archeology Department, University of York. SRUK Yorkshire Constituency.

More info:

https://www.york.ac.uk/archaeology/centres-facilites/bioarch/

Author’s profiles: