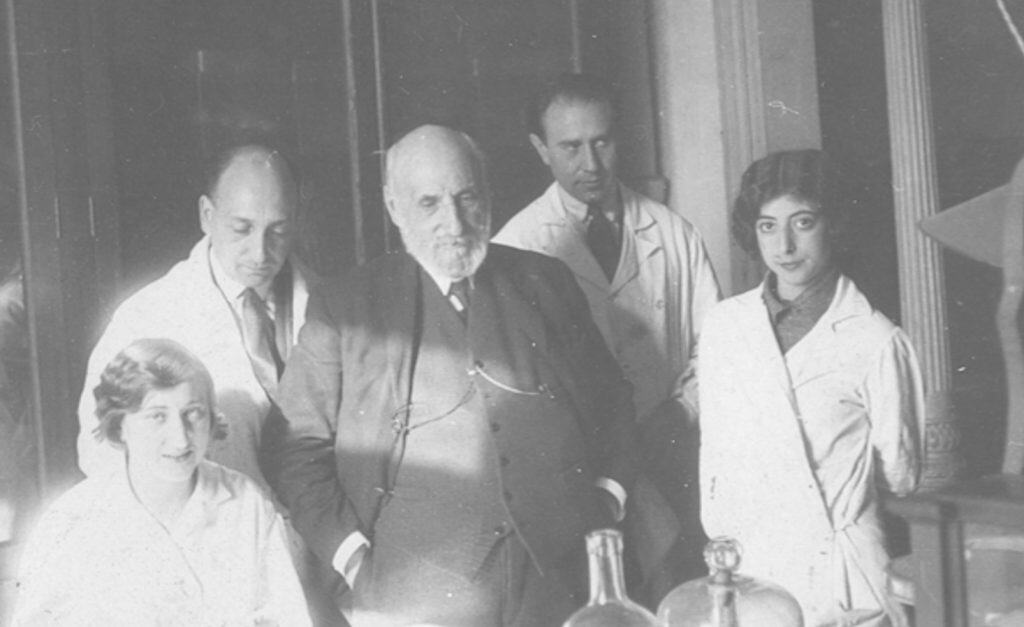

Cajal’s time (1852-1934) wasn’t known by the opportunities offered to women in any scientific area. This is a reflection of broader societal norms and gender biases in the scientific community of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where women faced substantial barriers to participating in formal scientific education and research.

Although Cajal’s own views on women in science were not particularly progressive by today’s standards, and most of his collaborators and mentees were men, a limited number of female scientists spent part of their careers at the heart of the Cajal School. It’s important to highlight that these women were not as prominently recognized during their time, but still managed to engage in neuroscience research and their pioneering role in the field deserves to be recognised.

Let’s discover some of these figures:

- Manuela Serra. She was one of the assistants at the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas. Even though Manuela Serra was not a doctor or senior researcher, she was the sole author of an article published in the journal of the laboratory in 1921. This was maybe the reason why Santiago Ramón y Cajal mentioned Manuela Serra in his list of disciples dated in 1922, and she was also included as a member of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas in successive years.

- Soledad Ruiz-Capillas. The first Spanish woman with a university degree that worked in Cajal’s circle was María Soledad Ruiz-Capillas. In 1928, Dr. Ruiz-Capillas became part of the research group of the neuropathologist and neuropsychiatrist Gonzalo R. Lafora at the Instituto Cajal (nominally, Laboratory of General Physiology). Between 1928 and 1930, María Soledad Ruiz-Capillas worked under the direction of Gonzalo R. Lafora and his assistant Julián Sanz-Ibáñez, studying the neural centers involved in sleep pathologies. Specifically, she collaborated in studies of the diencephalic thermal centers in the cat, sleep problems derived from infundibular and mesencephalic lesions, and how infusing diverse ionic solutions and other substances (calcium, potassium, magnesium, luminal, opioids) affected sleep, in this case employing new direct approaches to the IIIrd ventricle designed by the group. She never published a scientific paper and subsequent Lafora’s scientific communications in this field didn’t include Dr. Capilla’s as an author, showing again the underestimation of female contributions in the field.

- Laura Forster. Laura received her MD from the University of Bern in 1894 and worked for 6 years at the Institute of Pathology where she published her first paper. In 1911, according to Cajal and Forster, she worked for “a few months” at the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas or Cajal’s laboratory. Indeed, in the very first lines of her third scientific paper, Laura Forster declares that Santiago Ramón y Cajal suggested she focused her research in the lab on whether the degeneration of nerve fibers after traumatic lesion of the spinal cord in birds corresponded with events observed in previous studies on mammals performed by Cajal himself and others. In fact, Forster’s study was the first time that neurofibrillary techniques were applied to birds for this purpose and her results demonstrated similarities with the process in mammals, although these occurred more rapidly in birds, describing both degenerative (retracted fibers with varicose “in ball” endings) and regenerative processes (fine nerve sprouts that penetrated the scar and the necrotic zone). Cajal cited the work carried out by Laura Forster’s in his laboratory at least three times and her studies were continued by Lorente de Nó and Manuela Serra. The career of Laura Forster underwent a drastic turn in 1912 and, when the First Balkan War was declared, she traveled to Epirus to enlist as a nurse, since women couldn’t serve as physicians at the war front. From that moment onwards, the life of Laura Forster was linked to war. After all her sacrifices and remarkable life, she was recognised as an icon for female physicians in Australia and the Commonwealth.

One of Cajal’s most acknowledged disciples is Pío del Río-Hortega, widely recognized for his discovery of microglia and oligodendrocytes. He was open to collaborating with both male and female scientists, and his research group included a few women, which was somewhat progressive for his time.

- Dorothy M. Russell. In 1919 Dorothy Russell was one of the 30 women accepted in The London Hospital Medical College. She specialized in Pathology and researched mainly renal physiology and kidney diseases, publishing some papers. She then moved fields to the nervous system and was trained in neurophysiological techniques learning Río-Hortega techniques. In 1935, Dorothy Russell was the first to grow glial tumor cells in culture. At the start of WWII, Dorothy Russell became the main direct collaborator of Pío del Río-Hortega until he left Oxford for South America and even succeeded him as the head of Neuropathology at the Radcliffe infirmary. Both worked hard together, and it was an outstanding opportunity for Russell to further develop her skills in metallic impregnations devised by the Spanish Neurological School. In 1944, Dorothy Russell was the first woman to achieve the status of Professor and Chair of Pathology in Europe.

Even though the number of women in Cajal’s school is not huge, these women are some examples (there are a few more) of female scientists that contributed to the advance of neuroscience.

More resources:

- Women in Cajal’s School: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroanatomy/articles/10.3389/fnana.2019.00072/full#h3

- Manuela Serra: https://nah.sen.es/vmfiles/vol8/NAHV8N2202039_48EN.pdf

- Women disciples of Pío del Río Hortega: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroanatomy/articles/10.3389/fnana.2021.666938/full

- Comic about Women in Cajal’s School: https://www.ucm.es/otri/comic-ellas-tambien-son-escuela-cajal-ucm