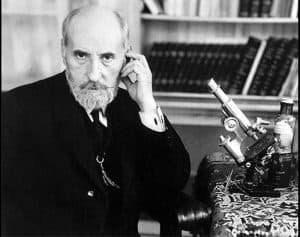

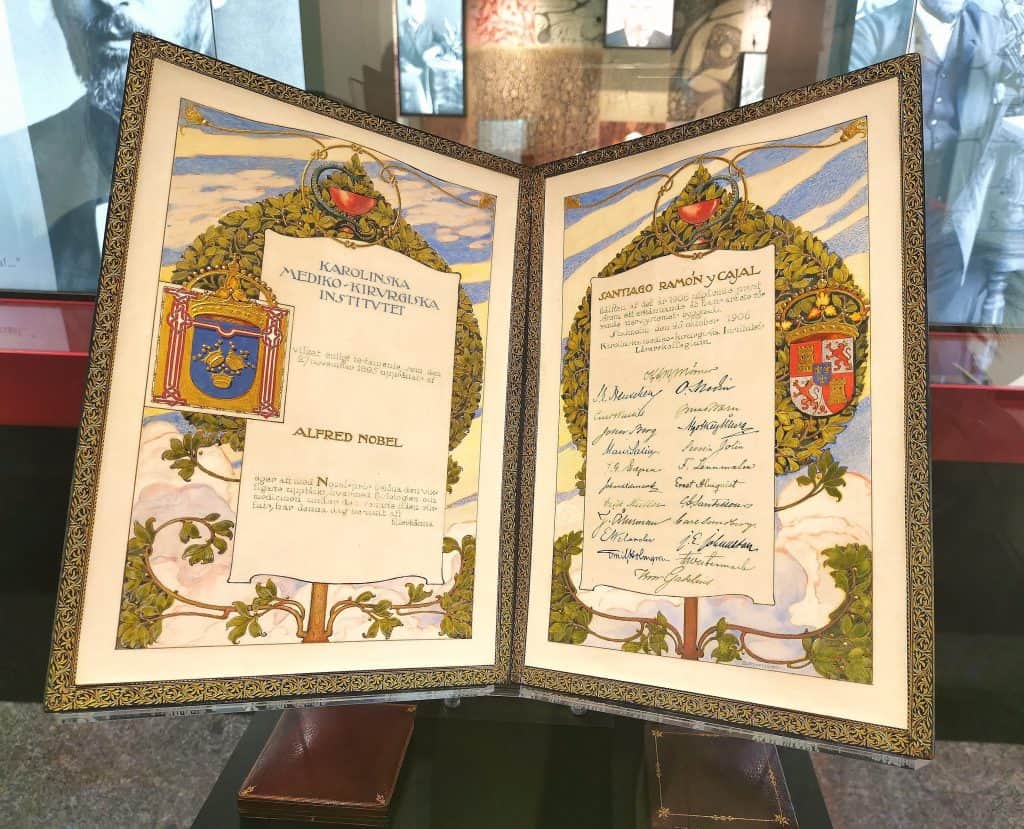

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, jointly with Camillo Golgi, in recognition of his groundbreaking work that laid the foundation for modern neuroscience. Cajal’s discovery of the Neuron Doctrine—which identified the neuron as an individual, isolated cell—was made possible through the use of Golgi’s staining technique. Although the Nobel Prize was awarded to both scientists for their complementary research, it was later established that Cajal’s theory was the correct one, and it eventually became dominant in the field. Despite the early resistance to his ideas, Cajal’s contributions were eventually acknowledged, and his work—especially his detailed drawings illustrating the brain’s structure and function— shaped the future of neuroscience. The Nobel Prize not only validated Cajal’s theories but also helped elevate neuroscience as an independent and respected scientific discipline.

Regarding Cajal’s trip to Stockholm, it’s interesting to note that he was initially reluctant to make the journey. Known for his humble and reserved nature, Cajal preferred to remain focused on his work rather than seek public recognition. Nevertheless, he eventually agreed to travel. The journey itself was no small feat in 1906: Cajal undertook a long and uncomfortable trip, combining trains and boats over several days to reach Stockholm. Once there, he also visited Uppsala University, where he delivered a lecture to the scientific community. Uppsala University, the oldest and one of the most prestigious institutions in Scandinavia, has a long-standing tradition of inviting Nobel Laureates to deliver lectures or talks before or after the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm. During his trip, Ramón y Cajal, along with Golgi, visited Uppsala after the Nobel Prize ceremony, which is held annually on December 10th—the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

Given that the Nobel Laureates arrived in Uppsala on December 15th, five days after the ceremony, it’s clear that Cajal’s trip was not limited to the Nobel event itself. It was also filled with numerous science-related activities and dissemination talks, spanning both Stockholm and Uppsala counties in Sweden.

Extract from the Uppsala Newspaper. Monday, 17th of December, 1906. Translation into English: “Nobel Laureates visit Uppsala. Nobel laureates Professors Ramón y Cajal and Golgi, the latter accompanied by his wife and an assistant, visited Uppsala on Saturday (15th of December). The notable travelers were accompanied by Spanish Legation Secretary, Mitjana. During the visit, the city’s sights were visited, including the university library, under I. Collijn’s management.”

Returning to the Nobel Prize ceremony and the interaction between Cajal and Golgi during the trip, it is believed that they did not engage extensively with each other during the events surrounding the ceremony. While mutual respect was likely expressed by both, during his Nobel lecture (“The neuron doctrine – theory and facts”, December 11, 1906), Camillo Golgi once again emphasized the reticular theory, subtly attempting to downplay Cajal’s discoveries and theory. In contrast, during Ramón y Cajal’s Nobel lecture (“The structure and connexions of neurons”, December 12, 1906), he respectfully refuted Golgi’s claims by presenting additional evidence supporting the neuron doctrine. Their differing views likely created an awkward atmosphere surrounding their shared Nobel Prize, and it’s easy to imagine some tension during their respective lectures. We highly encourage readers to explore both Nobel lectures -available in the above links- and form their own impressions.

The rest was history: Ramón y Cajal became the first Spaniard to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, marking a historic milestone for both his career and the field of neuroscience. His contributions have left a lasting legacy, and his discoveries continue to shape our understanding of the brain’s structure and function nowadays. It is also worth mentioning that his artistic talents in drawing the structure of neurons across different animal species were, and continue to be, inspiring, representing a fusion between art and neuroscience. A copy of Ramón y Cajal’s Nobel Laureate Diploma is shown above.