Santiago Ramón y Cajal is considered the father of modern neuroscience and was the first Spanish who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. His scientific work was revolutionary and some of his hypotheses are still valid nowadays.

The drawings selected for the exhibition were based on three important theories and hypotheses Cajal described (the neuronal theory (1890), the law of dynamic polarization (1897) and the discovery of dendritic spines (1888)), as well as to show the extensive work he has done during his whole research career.

A few years after finishing his PhD, in 1883, Cajal moved to Valencia, as he obtained a position as Lecturer in the Anatomy Department at the Faculty of Medicine. Interestingly, his earliest research work was about the cholera microbiome. A cholera pandemic affected people in Valencia in 1885, and the council contacted him to do some research about the disease and its prevention.

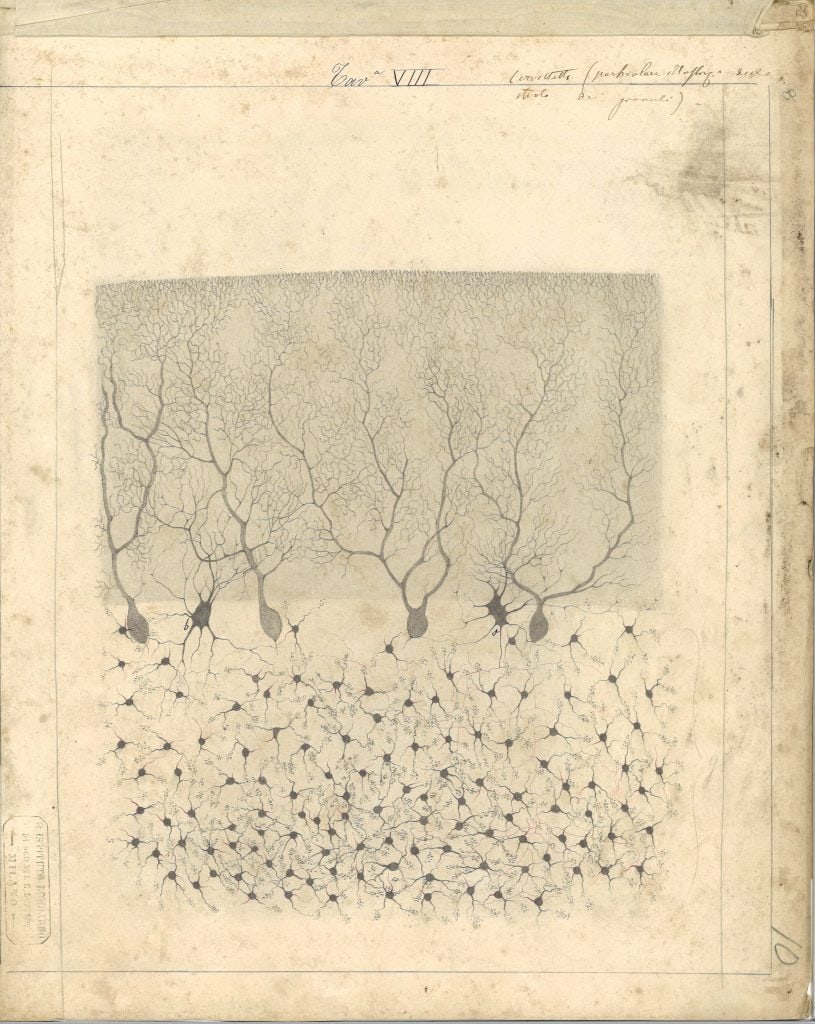

On the following sections we are discussing Cajal’s more relevant theories illustrated by some of the drawings you can observed at the exhibition. Apart from this, you can also find a selection of drawings that aims to reflect the extensive work Cajal has done. He not only studied the whole brain, from the cortex, to the thalamus, hippocampus, spinal cord or cerebellum; but also different cellular types of the central nervous system (neurons and glia).

The Golgi method

In 1874, Camillo Golgi published his scientific findings on the cerebellum in ‘On the fine anatomy of human cerebellum’ detailing the dendritic tree of Purkinje cells and describing the cytoarchitecture of the cerebellar cortex. He used a reaction, known as the black reaction (reazione nera), which allowed neurons to be stained in their entirety, providing an unprecedented view of their morphology. His method (the Golgi method) revolutionized histological studies and became the foundation for future discoveries in neuroscience. Nowadays there are researchers who still use this technique.

In 1887, Cajal became Professor of Histology and Pathological Anatomy at the University of Barcelona. During that period, he was introduced to Golgi’s staining method through the Spanish scientist Luis Simarro, who had applied it while working in Ranvier’s laboratory in Paris. During a visit to Simarro’s laboratory in Madrid, Cajal had his first opportunity to observe neural tissue stained using the black reaction. He was immediately impressed by its potential and later recalled in his memoirs:

“I was astonished by the marvellous revealing power of the silver-chrome reaction.” Book. ‘Memories of my life / Recuerdos de mi vida: Historia de mi labor científica’ Santiago Ramón y Cajal. 1917

Despite its revolutionary potential, Golgi’s staining method had significant limitations. It was highly inconsistent, producing successful results only sporadically. Determined to overcome these issues, Cajal systematically improved the technique through several modifications. These refinements, documented in his 1888 and 1889 publications, transformed the black reaction into a reliable and widely used method. In Cajal’s hands, Golgi’s method represented the main tool that made it possible to change the course of the history of neuroscience and marked the birth of modern neuroscience.

The neuronal theory

Before Cajal’s revolutionary neuronal theory, scientists accepted the reticular theory as a possible explanation of how the brain was organized. This theory postulated that neurons formed a giant net with their axons fused one to another one in order to transport the neuronal signal from one to another one. Golgi was one of the main defenders of this reticular theory.

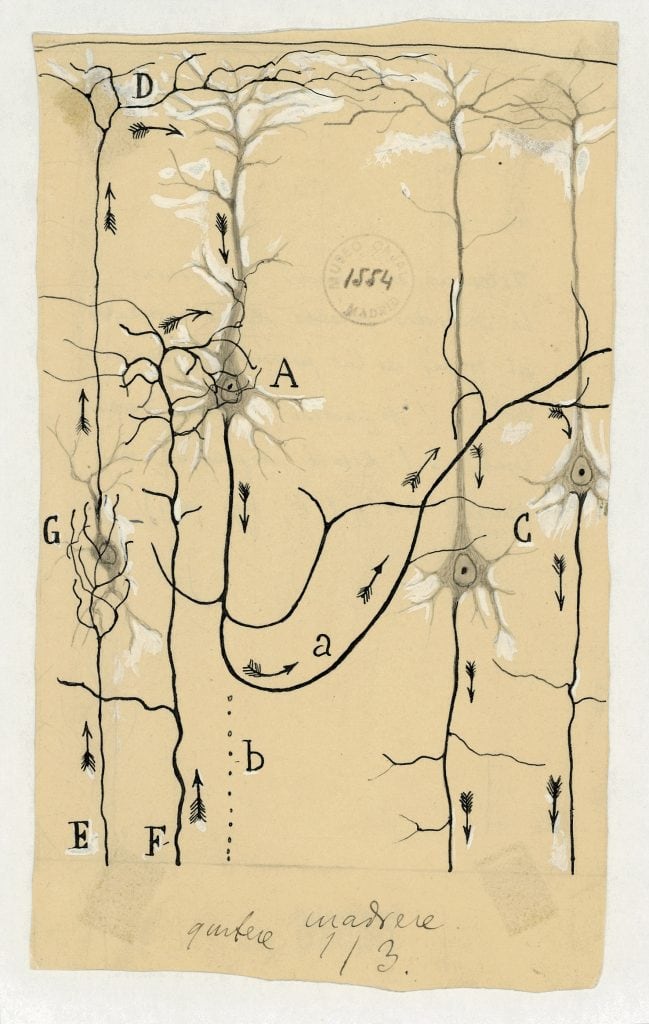

Cajal demonstrated that the reticular theory was not correct, that nerve cells are independent elements with their dendrites and axons that are not anastomosed, being the neuronal signal propagated by contact, not by continuity. This is what we now call “synapsis”. This idea was revolutionary and was illustrated in one of the most important drawings of the exhibition, shown and explain in Figure 2.

If you want to know more about the neuronal theory, we recommend these two scientific articles:

- Golgi and Cajal: The neuron doctrine and the 100th anniversary of the 1906 Nobel Prize. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(06)01203-6.pdf

- Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0361923006002334

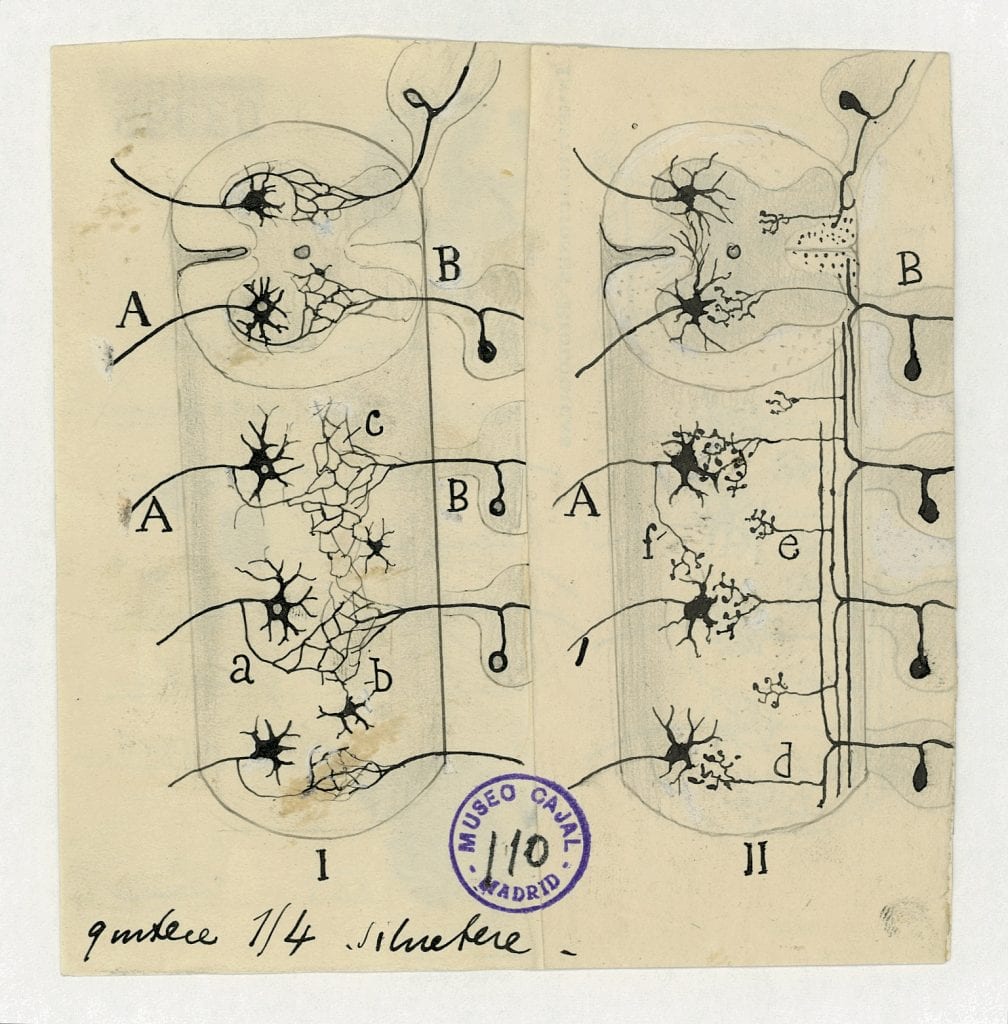

The law of dynamic polarization

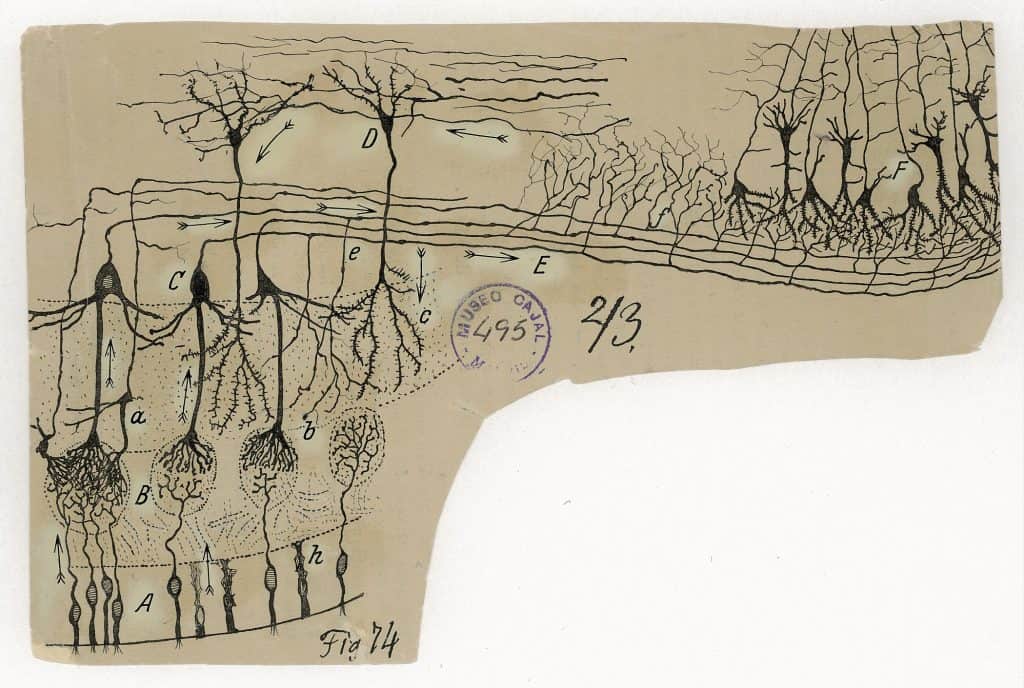

If you visited the exhibition, you probably would have observed a few drawings similar to the one in Figure 3, representing a group of neurons from specific brain regions with different letters and arrows. In this example, Figure 3 represents a diagram of the olfactory bulb and medial temporal cortex, in which the arrows are representing the direction of the neuronal impulse.

This figure is an example to represent the law of dynamic polarization, probably Cajal’s second most important contribution. He presented his first hypothesis in 1891 in a conference in Valencia, but the law was not enunciated until 1897.

“The transmission of nerve impulses occurs from dendritic branches and the soma to the axonal process. Thus, every nerve cell has a receptive apparatus, the body and dendritic processes; a conductive apparatus, the axon; and an emitting apparatus, the varicose terminal arborization of the axon.”

What Cajal proposed is that neurons are individual units that transmit their impulses in a specific direction, from the dendrites to the cell body, and to the axons, before moving into the next cell. Another example is shown in Figure 4 on the left. This new concept was tremendously revolutionary for its time and a major step forward for neuroscience.

Cajal’s law of dynamic polarization and the neuronal theory contradicted the reticular theory, largely accepted by the scientific community at that time, which took decades to be unanimously accepted. Cajal wasn’t just fighting a scientific idea; he was pushing against an established dogma, technological limitations (he only had his microscope), and academic resistance. That’s part of what makes his story so legendary.

If you want to know more, we recommend this article:

- Cajal and the Conceptual Weakness of Neural Sciences. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4588005/

The discovery of dendritic spines

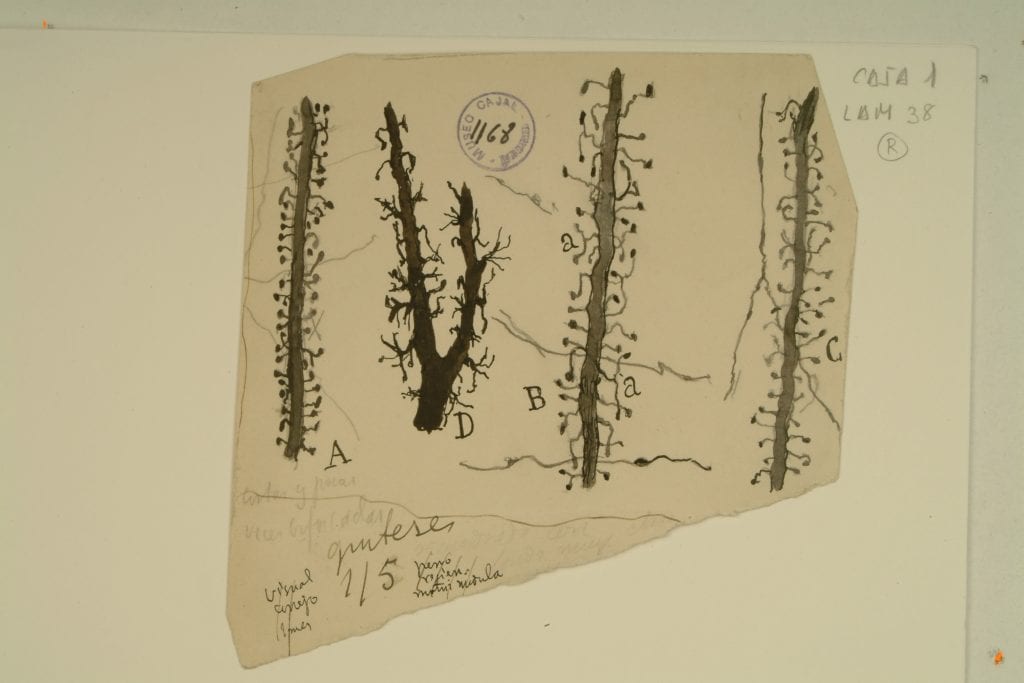

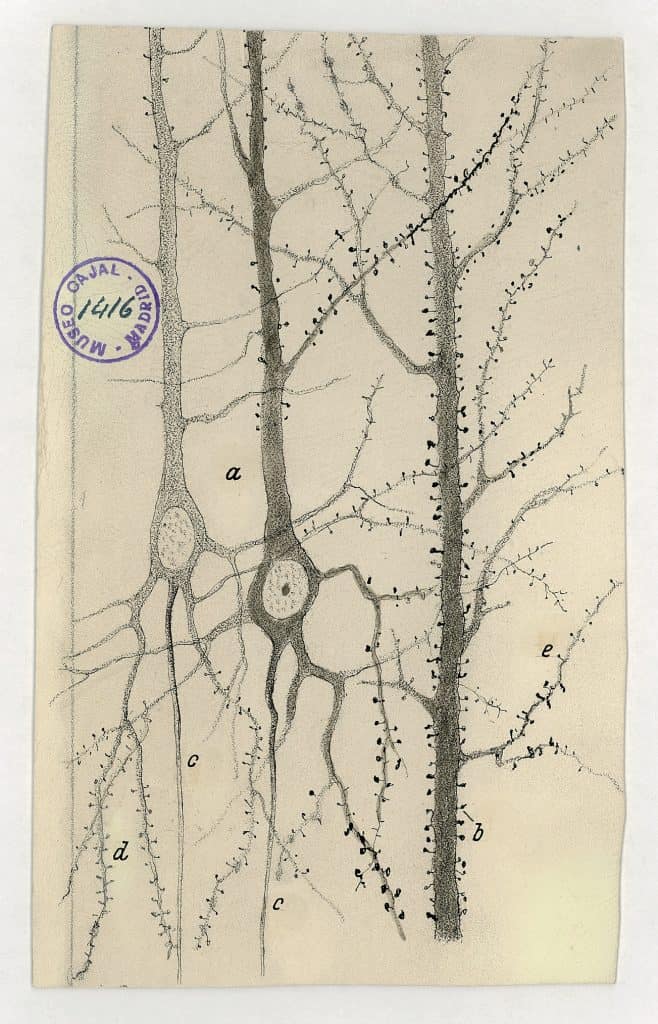

Cajal not only improved the Golgi staining technique, but he also identified the dendritic spines. Where every histologist thought these spines were just artifacts of the staining process, not real structures, Cajal (one more time against the established) hypothesized that those structures were an important part of the morphology of the neurons. He also believed they were important for synaptic transmission.

He was right, and those tiny protrusions were called “spines”. They are located at the dendrites and nowadays it has been demonstrated that they are incredibly relevant for brain plasticity and processes such as learning or memory.

You can find three drawings that illustrate these dendritic spines. Figure 5 showed different types of dendritic spines and figure 6.

He recognized their importance decades before modern tools (like electron microscopes and fluorescent imaging) confirmed their structure and role.

If you want to know more visit:

- The discovery of dendritic spines by Cajal – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroanatomy/articles/10.3389/fnana.2015.00018/full

- Viewing the brain through the master hand of Ramon y Cajal – https://www.nature.com/articles/nrn1010

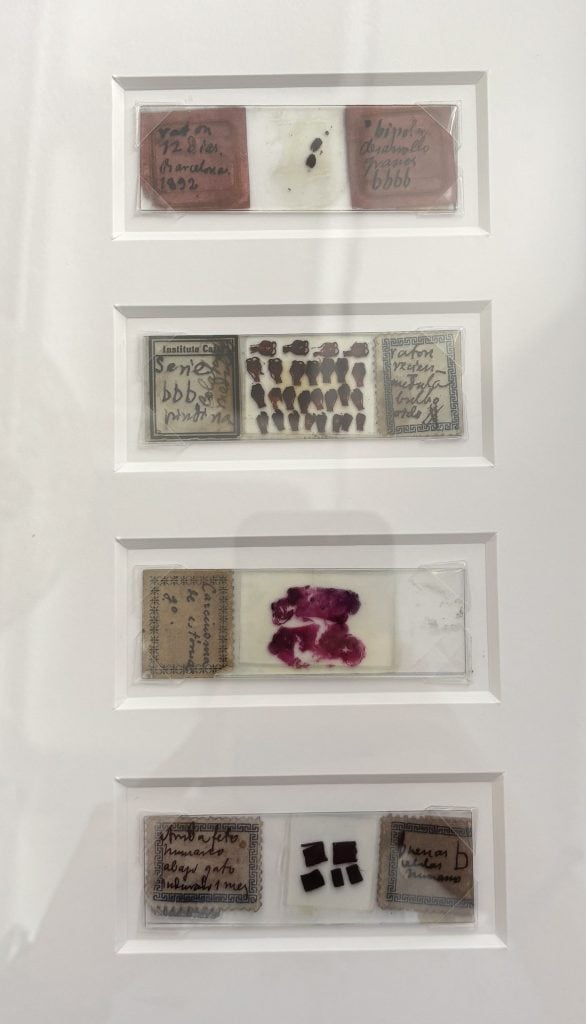

Cajal’s scientific preparations

If you’ve visited the exhibition you have had the chance to observe four different scientific preparations from Cajal’s. These are facsimiles, based on his original ones. If you are a good observer and had tried to read the slide labels, you might have come across a code that he had to classify his samples. You can observe letter b (meaning good in spanish (bien)) in all four preparations. Depending how good the sample is you will observe from one to four b on each of the slides.

There are more than 4,500 histological preparations from Cajal, but if you want to know more about the different stainings or the different types of tissues he used, we encourage you to check “The histological slides and drawings of cajal” (link here)